[ad_1]

The family of a man killed by a guard at a military base in Kodiak is still searching for answers more than two years after his death. The Navy SEALs have video of the shooting, but they stonewalled the family’s request to see it. So now, the family says the only hope is a federal lawsuit.

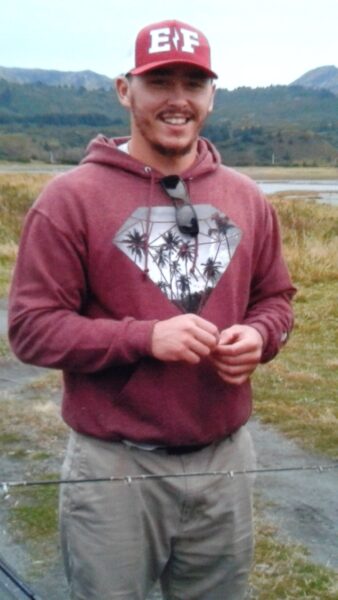

In the spring of 2020, Tony Furio was driving to collect firewood in Chiniak, near where the road ends on Kodiak Island. Furio and his son, Jason Weinberg, loaded the truck with sandwiches and a big bag of potato chips if they got hungry along the way.

“I can remember on the way back he started laughing and I go, ‘What are you laughing about?’ He said, ‘Dad, you better have some of these before I finish the whole bag.’ It was just a fun time,” Furio said.

Wynberg died a few months later.

On a warm night in June, the 30-year-old man wandered into Kodiak’s Naval Special Warfare Detachment — known to locals as the SEAL base.

According to investigators, Wynberg was armed with a pair of kitchen knives. He hit them on the glass of the guard house where a guard was isolated. The guard repeatedly ordered Wynberg to leave, the report said. Wynberg started walking. Then, still carrying the knives, he turned and walked towards the guard, who shot and killed him. A later blood test showed Weinberg was intoxicated — he had a blood alcohol content of .11 — and had marijuana in his system.

In January of this year, a joint state and federal criminal investigation concluded that Wynberg’s killing was justifiable because the guard acted in self-defense.

But Wynberg’s family still has questions. The army has not told them anything. This prompted them to file an RTI application to see the results of the investigation. Still, he refused to show them the surveillance video that captured the last moments of his son’s life.

“We’re at peace in a lot of ways, but not necessarily at peace about what happened,” said Wynberg’s stepdaughter, Esther Furio.

That June night is the focus of a lawsuit filed against the U.S. government this summer by Winberg’s widow, Becky Winberg. She declined the interview. The Furios are not listed plaintiffs, but say they support the suit.

The family of Jason Weinberg was represented by attorneys Jeffrey Robinson and Ashley Sundquist of the Anchorage law firm Ashburn & Mason.

The original complaint named the United States, the US Navy, and Petty Officer Bradley Udell, who shot Wynberg, for wrongful death and negligent homicide. The latter two were dismissed as defendants, but a judge ruled last month that the case against the US could continue, noting that the US had “not put forward what it only knows about the circumstances surrounding the shooting”.

The U.S. Attorney’s Office declined to comment on the case.

Tony Furio said the lack of transparency was painful.

“When you think you’ve almost got it, it’s not because that finality isn’t there,” he said. “It’s hard, that’s all.”

In July, the Naval Criminal Investigative Service, or NCIS, released hundreds of pages of material in response to FOIAs filed by KMXT, CoastAlaska and Vinberg’s family.

But the report has been heavily redacted – all the names have been blacked out, and in some places, it’s hard to even understand what it says. Although surveillance video footage of the incident was repeatedly referenced in NCIS’s report, the military has so far refused to release it to KMXT or the family. After 9 months it says the video is still under review.

KMXT filed another FOIA request for the video in September, this time with the Naval Special Warfare Command. Alaska state troopers declined to release the tape or additional materials related to the case, deferring to the level of corrections established in the full report by federal investigators.

That’s not normal. These days, when a government official kills someone in the line of duty — and when it’s caught on video — authorities almost always release it.

Rich Curtner is a longtime public defense attorney in Alaska with experience representing people who have been shot by police officers. He was not involved in Weinberg’s case, but he said releasing body camera footage or surveillance video when it becomes available has become an important protocol for departments across the country.

“When an incident is documented, it can be made public in a timely manner — not two years, three years, or a whole process of going through the records,” Curtner said. “It should be released publicly as soon as possible.”

Curtner points to cases like the 2019 shooting of Bishar Hasan by Anchorage police officers as an example of how seeing what happened changed the perspective of the shooting.

In Hassan’s case, dashcam video showed officers immediately firing what was later determined to be a BB gun from his waistband. Minutes passed before someone administered first aid after multiple rounds were fired. The footage was not immediately available to family members or the public.

Curtner said making information available to the public can confirm a department’s account of events and whether an officer’s action is warranted.

“Unless you watch the video you can’t tell the difference between an overreaction or a belligerent and dangerous person,” he said. “Then you know how that person behaved.”

Page after page of NCIS’s report on Weinberg’s death includes interviews with his family, friends and colleagues — even some people who didn’t like him. There is information about past legal dust-ups and drug use, mostly from his youth.

Tony Furio said his son isn’t perfect, but for all the questions investigators have asked about him, the family hasn’t been able to ask their own questions about what happened to him.

Esther Furio said the process is something no family should have to go through.

“When you lose someone closest to you, it’s not like, ‘OK, it’s over,'” she said. “It’s always there, and the memories and the pain are there. But when it goes on for so long, it feels like you can’t really grieve because there’s no end to it.”

This year, on the second anniversary of the shooting, the Furios traveled to Kodiak’s Fort Abercrombie State Park. Esther Furio had created a floating flower arrangement that they placed together in the water beneath the park’s cliffs.

Tony Furio said he loves talking to his son at Abercrombie and has tried to find peace where he can. Since the night he learned his son died, he has said two prayers — one for forgiveness for the guard who shot his son and the guard’s family.

“Not that they had anything to do with it, but their lives, our lives, everyone involved with Jason has changed,” Furio said. “That the truth of God may be known at last.”

More than two years later, he said, he’s still waiting for that prayer to be answered.

Editor’s note: This story Co-produced by American Public Media and KMXT.

[ad_2]

Source link